Every year, the world gathers under the UN umbrella to talk about climate. Numerous delegations arrive at the Climate Change Conference, known as COP – Conference of the Parties – from all continents. Neon slogans like "Green Future" and "Net Zero by 2050" shine in the pavilions, and speeches about solidarity, innovation, and new goals are heard. But behind the closed doors, a completely different story begins, full of political bargaining, fears, and uncomfortable compromises.

EcoPolitic decided to look at how well world powers are implementing the main goal of the Paris Climate Agreement and fulfilling their commitments. We have analyzed what factors influence decision-making within countries and in the international arena, as well as what reasons prevent effective containment of global warming.

A promising start

December 12 will mark 10 years since the adoption of the Paris Climate Agreement at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in France. It is called a landmark document because for the first time in history, a legally binding agreement brought together an absolute majority – 195 countries – to fight climate change and adapt to its consequences. All of these countries pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to jointly prevent climate warming by more than 2°C by the end of the century compared to pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Climate Agreement was supposed to replace the Kyoto Protocol. Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, however, all countries, regardless of their level of economic development, have undertaken to reduce harmful emissions into the atmosphere.

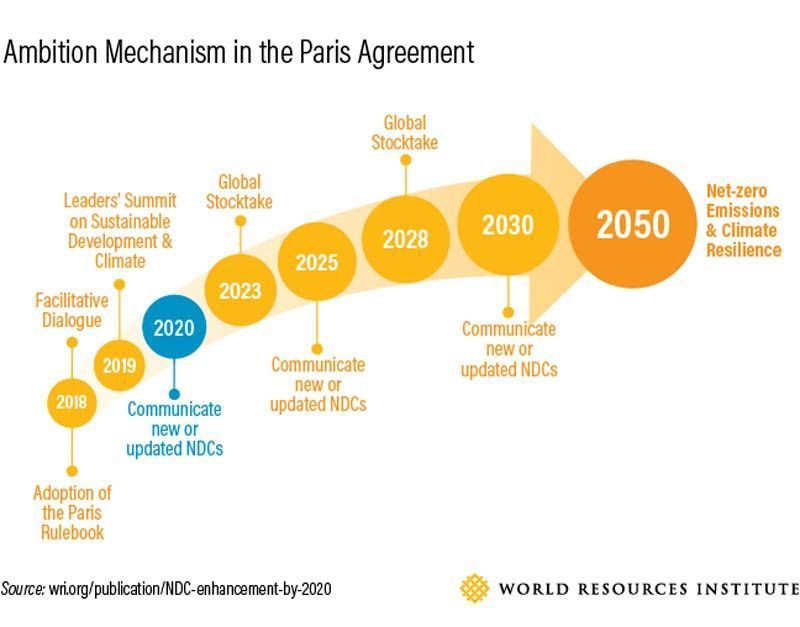

According to the Paris Agreement, every 5 years, starting in 2020, signatory countries must submit their national climate action plans. These are known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). And each time these plans have to become more ambitious than the previous version. However, each country has to determine its own policy to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

When the economy trumps the environment

It is easy to declare the goal of "For all that is good, against all that is bad," but when it turned out that the implementation of the Paris Agreement requires significant economic and social transformations, it turned out that many people were not ready for it.

The first major shock occurred when the first country to withdraw from the agreement in 2020, and it was the United States of America. US President Donald Trump, who made this decision, said he believed that "the economic restrictions it [the agreement] imposes on American workers, businessmen, and taxpayers are unfair." He noted that he wanted to protect the interests of American companies operating in the field of mineral extraction.

The next "stumbling block" was the issue of finance. The Paris Agreement stipulates that developed countries should take a leading role in providing financial assistance to countries that have fewer resources and are more vulnerable. Funding should be provided in two main areas:

-

to support the energy transition;

-

for adaptation to climate change that has already occurred.

And each of them requires significant financial resources and large-scale investments. This is where the most heated debate broke out, culminating in the COP29 conference last year.

The first hotly contested issue was the division of countries into developed and developing ones. Currently, the latter category includes Saudi Arabia and other oil states, as well as China and India. According to the EU and others, many of these countries should not be beneficiaries of financial climate aid, but rather its donors.

The second very controversial point is the agreement on the amount of the collective quantified goal of climate finance (NCQG – New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance). In 2009, several developed countries and the EU agreed to mobilize $100 billion a year by 2020 to help developing countries. However, they managed to fulfill this goal with a 2-year delay.

In addition, poorer countries at COP29 insisted on increasing the amount of funding. According to experts, it should amount to $1.3 trillion per year.

Victims and perpetrators at the same table

Climate negotiations at the COP conferences have become a mirror of the world's stark inequalities in recent years. Since decision-making is based on consensus, this means that any country can put on the brakes at any time. Even if 194 countries are ready to recognize the need to abandon fossil fuels, one – say, Saudi Arabia or Russia – can say no. And then, in the final text, "phase-out" turns into a soft wording – "gradual transition."

In this compromise, the main thing – the urgency – disappears. The global system designed to save the planet is moving at the snail's pace of diplomatic approvals.

The island states, which are literally going underwater due to global warming, are not asking for promises, but for compensation for the "loss and damage" caused by climate change. Next to them are representatives of countries that are rich in oil and gas exports, and they propose to create new "green funds" to which they will collect money themselves.

At COP29, for example, countries agreed to create a $300 billion fund. It sounds like a breakthrough, but analysts immediately called it a "promise fair" because most of these funds exist only in the form of loans or political declarations. There is almost no money that can actually be spent.

So countries suffering from droughts and floods are hearing an old song called "Just wait a little longer." At the same time, fossil fuel exporting countries become the hosts of the next COP and present themselves as "leaders of the green transition". For example, in 2023, the climate summit was hosted in Dubai (UAE), and the following year Azerbaijan became the host of COP29.

“The COP28 communiqué is not legally binding. Nothing that happened in the negotiation rooms in Dubai changes the situation on the ground in nearly 200 countries whose representatives attended. What really matters are politics and money – what these leaders do when they return home,” – this is how a group of experts assessed the outcome after the climate summit in the UAE.

Opposing currents in global climate policy, or the "Trump effect"

As the past decade has shown, trust is the main currency of climate diplomacy.

When Donald Trump first announced the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, he did not just upset the balance – he opened a Pandora's box.

The world saw that commitments that were considered unbreakable could be canceled with a single signature. Since then, climate policy has become more of a symbolic gesture than a guaranteed action.

Even after the return of the United States under President Joe Biden, other countries were in no hurry to raise their ambitions to combat climate change. The logic is clear: why make the effort if the political wind can change again tomorrow?

And, as time has shown, they were right: Trump, after his second inauguration, was one of the first to sign an executive order to re-exit his country from the Paris Climate Agreement. Moreover, the administration of the current US president has also turned its domestic climate policy 180 degrees and has chosen to increase fossil fuel production and reduce clean energy projects.

And this decision of the world's largest player significantly affects the formation of climate policy in other countries against the backdrop of a new geopolitical reality.

What's wrong with the NDC?

The Paris Agreement of 2015 was supposed to be a new beginning. The countries abandoned the idea of top-down approach, when someone sets quotas for everyone, and introduced the principle of voluntariness.

Each country had to decide for itself how much emissions to reduce and how fast. This sounded like a manifestation of sovereignty, but in practice it turned into a geopolitical game of "ambition" where telling numbers are more important than real actions.

Compromise on the verge of a foul

In most countries, the NER is not just an environmental document, but the result of a political compromise between ministries, business, and the public. Ministries that deal with environmental protection propose targets, economic departments "adjust" them, and energy and industrial lobbies try to leave as much room as possible for fossil fuels.

The result is a document in which beautiful wording like "achieve climate neutrality by 2050" or "increase the share of renewable energy" often lacks clear mechanisms for their implementation.

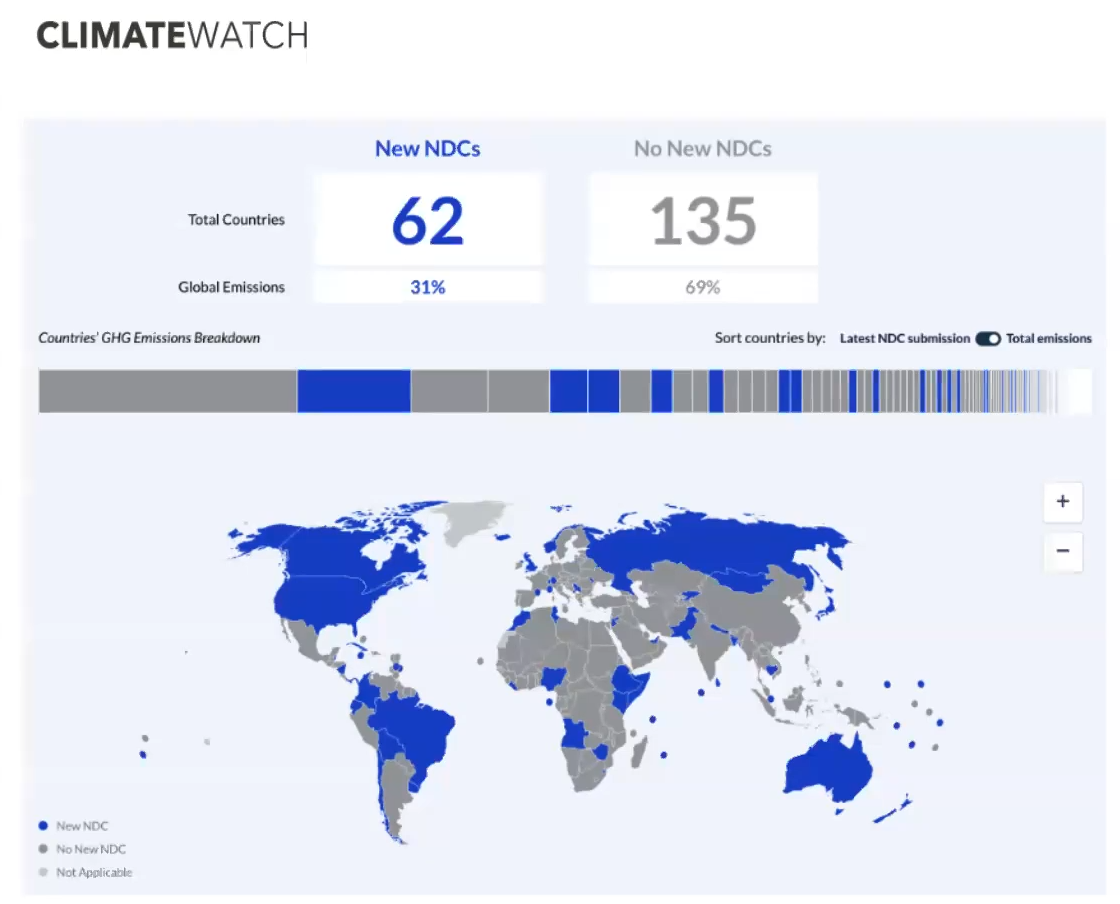

According to the World Resources Institute, only 62 countries, which produce about 31% of greenhouse gas emissions, have submitted their updated NDCs so far. The other 135 countries responsible for 69% of emissions, including some of the largest polluters – India and China – have not yet done so.

Source: climatewatchdata.org.

Only a few countries have NDCs backed by specific policy instruments (carbon taxation, RES incentives, etc.). The rest of the Nationally Determined Contributions are essentially just intentions.

Paper ambitions

NDCs are supposed to be updated every 5 years, and with each cycle, they should be more ambitious. But in practice, "updating" often means "repeating the old goals in a new cover".

Some countries submit only symbolic changes: a few percent difference in reductions or a "recalculation" of the base year to show better dynamics on paper.

The Climate Action Tracker regularly records that most national contributions are leading the world to a 2.4-2.6°C temperature rise, while the Paris Agreement promised to keep warming "well below 2°C."

This means one thing: the collective arithmetic does not add up. The reason is that countries are declaring less than they need to and acting more slowly than they promised.

Implementation is in question

Even those who set ambitious national contributions do not always fulfill them. The reasons for this can be very diverse: political cycles, economic crises, wars, business lobbies, and changes in governments.

In the United States, Trump's withdrawal from the Paris Agreement led to the curtailment of federal emissions reduction programs. In Australia, conservative governments have blocked energy reforms for years, citing "job protection." China is both increasing the capacity of wind and solar power plants and opening new coal-fired power plants.

As a result, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global CO₂ emissions reached a record 37 billion tons in 2024. This is the most obvious evidence that declarations do not translate into action.

What about Ukraine?

The first Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC1) stipulated that greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 would not exceed 60% of 1990 levels.

In 2021, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine approved the Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC2-2021). This document raised Ukraine's ambitions and set a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 35% of 1990 levels by 2030. At the time, the authorities did not even discuss this figure with industry representatives, who learned about it after the fact.

On June 12 of this year, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine presented the draft NEC2-2025. It envisages a 68-73% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in 2035 from 1990 levels. Such declared ambitious intentions were criticized by industry representatives. For example, the European Business Association (EBA) called for a review of Ukraine's NDC2, taking into account the current state of the Ukrainian economy. EBA representatives emphasized that climate goals need to be revised and adapted, as they must remain realistic and achievable in the context of a full-scale war.

Why do experts refer to the COP format as ineffective

-

The decision-making process is currently too slow. After last year's COP29, in an open letter, leading experts – including former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and former head of the UN climate program Christiana Figueres – stated that climate negotiations within the framework of the Conference of the Parties (COP) “no longer serve their purpose” and require urgent review.

“The current structure simply cannot deliver change at the exponential speed and scale necessary to ensure a safe climate future for humanity,” the signatories of the letter emphasized.

-

UN climate conferences are often more about image – passionate speeches, attractive pavilions, and loud declarations – than about concrete actions.

-

There is a high dependence on political circumstances, where, for example, a change of government in the United States, Brazil, or Australia instantly alters the positions of these countries.

-

There are no significant levers of influence on those countries that fail to fulfill their pledged NDCs. At present, there are no sanctions or enforcement measures.

-

Disproportionate influence: major states and corporations dictate the pace of negotiations and the agenda.

-

Financial inequality among countries and donor fatigue.

-

Excessive bureaucracy and formalism, as hundreds of pages of legally cautious wording often “smooth over” and obscure the real meaning. Each country then interprets these in its national policies at its own discretion.

Is There an Alternative?

Despite all the criticism, abandoning COP is currently impossible – it remains the only global platform where everyone meets. However, this format needs reform. Experts are proposing the following:

-

restrict the right of veto for individual countries;

-

introduce an independent system for verifying NDCs;

-

separate negotiations into technical (scientific) and political tracks to avoid deadlock.

Former US Vice President and current climate campaign activist Al Gore also agrees with the idea that the COP climate conference needs transformation. He considers it absurd that the chairmanship of UN climate negotiations is routinely passed to oil-producing states.

“One of the reforms I proposed is to give the Secretary-General [of the UN] the right to decide who will host the Conference of the Parties, rather than simply leaving it up to such voices as Vladimir Putin, and letting oil states in the Middle East decide who will host,” Gore said.

National Level

The driving force behind real climate action may come from so-called “pragmatic alliance” coalitions. There is already a practice where small groups of countries form blocs to accelerate action outside the COP framework. For example, the Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) is a coalition of countries that voluntarily forgo new oil licenses. It currently includes 15 member countries, 2 associate members, and 7 friend countries.

“Bottom-up” approach: subnational initiatives

Cities, regions, and individual corporations often move faster and more decisively than national governments. One prominent example of such initiatives is C40 Cities-a global network of the world’s major cities collaborating to combat climate change. The network brings together nearly 100 megacities, home to about one-fifth of the world’s population and responsible for roughly 70% of global CO₂ emissions. The goal of C40 is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, adapt cities to the impacts of climate change, and make them more sustainable, “green,” and livable.

U.S. states such as California and Massachusetts also openly opposed Trump’s climate policy, maintaining their commitment to the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement even after the U.S. withdrew from it.

After analyzing the 10-year period since the Paris Agreement was signed, we tend to agree with the opinion expressed by the American publication Foreign Affairs:

“The future of climate diplomacy will not depend on a single global accord among nearly 200 countries, but on a web of regional and sectoral agreements, partnerships, and incentives that actually spark change on the ground,” stated the article “A New Way to Fight Climate Change.”

Perhaps it is within this network-based logic that lies a chance to revive what currently appears to be a tired system of globally empty declarations.